“I had someone tell me I fell off/ Ooh, I needed that,” he sing-rapped on “Headlines” - a candid admission that his 2010 debut album Thank Me Later, despite contributing to his rapid rise, was far from his best work. None of his imitators were making it sound quite so easy, though by his own admission even Drake struggled to pull off this sound for a while. There’s a reason people were attempting to copy this template - the same reason Drake himself returned to this it repeatedly on future hits like “God’s Plan” and “Laugh Now, Cry Later.” “Headlines” captured Drake at his most accessible, his voice intuitively gliding over 40’s rippling synthesizers. To hear Drake tell it, his influence was already pervasive by the time Take Care dropped: “Soap opera rappers, all these n****s sound like all my children,” he declared in one of the album’s most impressively multi-layered lyrics. In the coming years he would become the North Star for not just rap and R&B but for all of pop music, inspiring countless young artists to explore their own emotional interiors through stylish genre hybrids. The impact of this pioneering approach would have been significantly less profound if Drake wasn’t also making fantastic pop singles. Drake was discarding the distinction entirely, blurring the two roles into one, with a grace and fluidity several steps beyond what key influence and collaborator-turned-frenemy Kanye West was doing on 808s & Heartbreak.

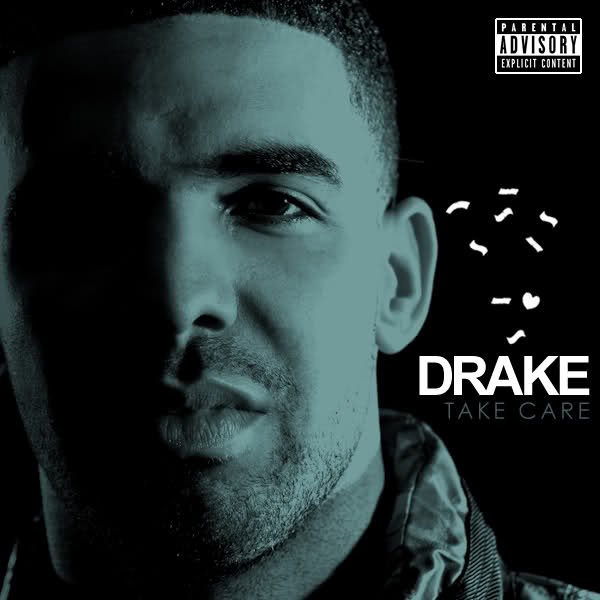

There was a binary in place it’s why T-Pain, who laid so much groundwork for Drake, felt compelled to name his 2005 debut album Rappa Ternt Sanga. A rapper who didn’t just sing his own hooks, a la Biz Markie, but routinely broke out into sweetly melodious choruses - and who sometimes went entire songs without rapping at all, instead languishing within pillowy production like a memory clouded by liquor and resentment? It felt radical, like a violation of an unspoken division of labor. Upon hearing “Best I Ever Had” two years earlier, when So Far Gone was rocketing him to fame, I had actually assumed Drake was an R&B guy at first. Kelly, and Usher, but from the opposite side of the singer-rapper divide, with uncommon vulnerability and passive aggression. Lauryn Hill, certainly Nelly, maybe, I guess? So when Drake tenderly crooned, “Bitch, I’m the man/ Don’t you forget it,” he was stepping into a long lineage of guys like Bobby Brown, R. Only once does he revert to the “hashtag-rap” flow he’d ridden to fame, and only to make a pointedly meta joke about his own improvement as a lyricist: “Man, all of your flows bore me/ Paint dryin’.” It is difficult to believe him when he insists, “I just been playin’, I ain’t even notice I was winnin’.” “Shot For Me”īy the time Drake blew up, there was a robust two-decade history of R&B singers carrying themselves like rappers, but rarely had a rapper come off so much like an R&B singer. The first words out of his mouth: “I think I killed everybody in the game last year/ Man, fuck it, I was on, though.”įrom there Drake surveys his kingdom with a now-familiar mix of ill-advised strip-club romance, humblebrags (and regular brags), wordplay both clever and groan-inducing, faux-wisdom that occasionally stumbles upon inspiration, and the airing of petty grievances, his rapping sliding now and then into little bursts of melody. Drake was well aware of his vaunted position, and he wasted no time letting us know he’d taken the throne as prophesied on that summer’s “I’m On One” - as if the album cover photograph of him somberly holding court with his goblet and his candle and his solid-gold owl did not sufficiently convey the point. With his second proper album Take Care, released 10 years ago today, he completed his ascendancy to the top of the mainstream rap food chain at a time when his status as a half-Jewish Canadian teen soap opera actor still felt novel.

It sounds immaculate.Īubrey Drake Graham had gone supernova more or less overnight by making softer, prettier music than your average rapper. Crafted by Kreviazuk and a young sonic visionary named Noah “40” Shebib, it’s a softer, prettier intro than you’d expect from a blockbuster rap album before 2011. Then comes Chantal Kreviazuk’s voice, sighing yet casually impassioned, painting streaks of neon on the music as she professes her irrational devotion. A sparse beat kicks up in the background, skipping and thudding as if we’re hearing it through the wall. Every piano chord is a shimmering pool, glassy on the surface, deep enough to get lost in.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)